Urban Subversion and Mobile Cinema

This paper introduces our bicycle-based cinema device—the “kino-cinebomber”— as a vehicle to re-imagine disused buildings and obsolete urban infrastructure for re-activated public leisure spaces.

Introducing the city, the river, and the “kino-cine-bomber”

In Coventry, the River Sherbourne is missing. Approaching the city from the west along Meadow Street at the perimeter of Coventry’s ring road, the Sherbourne unceremoniously disappears—underground. About a mile away, on the eastern edge of the city center, the Sherbourne re-emerges from a tunnel near where the ring road meets Sky Blue Way. Between these points, the Sherbourne transects Coventry, but invisibly; there is no sense of the river in its dense streets and pedestrianized central district. Here the Sherbourne is lost, hidden within a culvert system constructed after World War II. The once bucolic Pool Meadow adjacent to the Sherbourne was drained and now serves as Coventry’s central bus station and car park. Like numerous other urban watercourses, capping the Sherbourne had once been championed as visionary modern city planning—but no more.

This paper discusses our participation in efforts to re-expose the Sherbourne as a part of wider calls for urban leisure spaces via “daylighting” schemes for hidden urban waterways (Cox, 2007). Cox (2017) spotlighted campaigns to uncover hidden urban rivers and create pocket parks in Sheffield, New York City, Seoul, Auckland, Zurich and London, among other cities. These river daylighting schemes are widely celebrated for creating green corridors through cities, acting as flood-relief channels, restoring natural habitat, providing public parks and paths, promoting passive cooling to help combat the urban “heat island” effect, and complementing urban architecture. Where once city planners sought to cover urban rivers, it is increasingly fashionable to uncover them. They have become foci for intense debates about urban leisure spaces and architecture.

Although there is longstanding interest in urban spaces (e.g., Johnson & Glover, 2013), there has been almost no leisure scholarship on the relations between leisure and architecture (for exceptions, see Gilchrist & Ravenscroft, 2013; Walters, 2017). Where scholarship has focused on architecture and leisure spaces—e.g., skateboarding (Borden, 2001; Borden, Rendell, Kerr & Pivaro, 2001; Jones, 2016; Shirtcliff, 2015)—it has taken place largely outside of leisure studies. Others, have written of “social architecture” (Jones, 2009) that shapes, and is shaped by social, historical and political forces (see also Jones & Card, 2011). Yet, here too leisure takes a back seat to the political economy of urban space. Our research foregrounds leisure in urban spaces and architecture as activist politics.

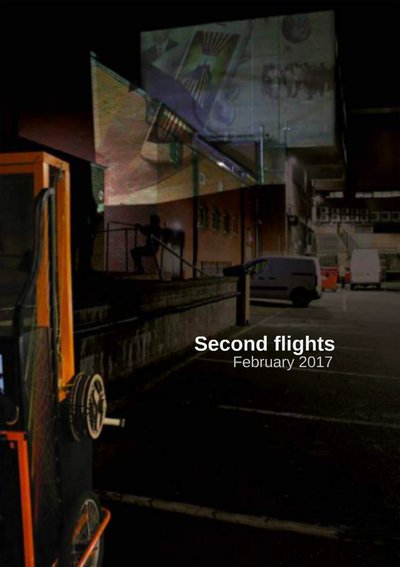

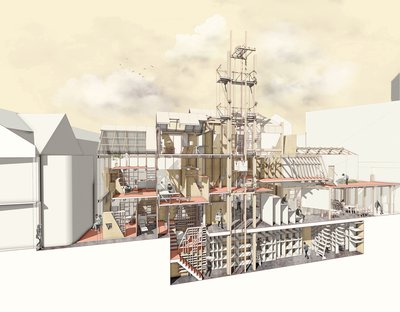

We collaborated with postgraduate architecture students in the (Re)Activist studio at Sheffield University to design and build a mobile bicycle cinema apparatus we call the “kino-cine-bomber” (see Figure 1). The kino-cine-bomber consists of a Danish (“Christiana”) freight bicycle with an added wooden tower to elevate a 2000-lumen projector; a car battery powers the projector, 50-watt sound system, and radio transmitter (for anyone wishing to listen in via radio). In a series of Situationist-inspired interventions (e.g.,détournement,dérive, constructed situation), (Re)Activist students pedaled the kino-cine-bomber through Coventry, first to suggest locations where the Sherbourne might be rediscovered. Then, in a second excursion, they projected architectural designs for (re)new(ed) communal spaces centralizing civic leisure spaces to counter the consumer-driven “zombification” of urban living (Lashua, 2016; Maak, 2015).

This paper discusses our participation in efforts to re-expose the Sherbourne as a part of wider calls for urban leisure spaces via “daylighting” schemes for hidden urban waterways (Cox, 2007). Cox (2017) spotlighted campaigns to uncover hidden urban rivers and create pocket parks in Sheffield, New York City, Seoul, Auckland, Zurich and London, among other cities. These river daylighting schemes are widely celebrated for creating green corridors through cities, acting as flood-relief channels, restoring natural habitat, providing public parks and paths, promoting passive cooling to help combat the urban “heat island” effect, and complementing urban architecture. Where once city planners sought to cover urban rivers, it is increasingly fashionable to uncover them. They have become foci for intense debates about urban leisure spaces and architecture.

The other Kine Bomber

Bibliography

- Borden, I.M. (2001). Skateboarding, space and the city: Architecture and the body. London: Berg.

- Borden, I.M, Rendell, J., Kerr, J., & Pivaro, A. (2001). Another pavement, another beach: skateboarding and the performative critique of architecture. In I.M. Borden (Ed.), The unknown city: Contesting architecture and social space. (pp. 178-199). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Butler T. (2009). ‘Memoryscape’: Integrating oral history, memory and landscape on the River Thames. In P. Ashton & H. Kean (Eds.),People and their pasts. (pp. 223-239). Basingstoke: Palgrave.

- Chee. Y.H. (2017).In praise of freespace. (Unpublished Master’s report). Sheffield University: Sheffield School of Architecture.

- Clarke, D.B. (1997).The Cinematic City. London: Routledge.

- Collie, N. (2011). Cities of the imagination: Science fiction, urban space, and community engagement in urban planning,Futures, 43(4), 424-431.

- Coulton, P., Huck, J., Gradinar, A., & Salinas, L. (2017). Mapping the beach beneath the street: Digital cartography for the playable city. In A. Nijholt (Ed.), Playable Cities. (pp. 137-162). Singapore: Springer.

- Cox, D. (2017). A river runs through it: The global movement to 'daylight' urban waterways.The Guardian.Retrieved from: <https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2017/aug/29/river-runs-global-movement-daylight-urban-rivers>.

- Craig-Thompson, A. (2017).The Institute for Transient Workers. (Unpublished Master’s report). Sheffield University: Sheffield School of Architecture.

- Debord, G. (1995[1958]).Situationist International Anthology (K. Knabb, Ed. and trans.). Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets.

- Debord, G. & Wolman, G.J. (2006[1956]). A user’s guide to détournement. In K. Knabb (Ed. and trans.), Situationist International Anthology. (pp. 14–21). Berkeley, CA: Bureau of Public Secrets.

- Dillon, S. (2007). The Palimpsest: Literature, Criticism, Theory. London: Continuum.

- Dovey, K. & Pafka, E. (2014). The urban density assemblage: Modelling multiple measures. Urban Design International, 19(1), 66-76.

- Easterling, K. (2014).Critical Spatial Practice: Subtraction. Berlin: Sternberg Press.

- Gilchrist, P. & Ravenscroft, N. (2013). Space hijacking and the anarcho-politics of leisure. Leisure Studies, 32(1), 49-68.

- Gilman-Opalsky, R. (2008). Guy Debord and ideology materialised: Reconsidering Situationist praxis.Theory in Action,1(4), 5-26.

- Hasegawa, J. (1992). Replanning the Blitzed city centre: A comparative study of Bristol, Coventry, and Southampton, 1941-1950. London: Open University Press.

- Hicks, J. (2007).Dziga Vertov: Defining documentary film. London: I.B. Tauris.

- Huskisson, L. (2016).The Urban Uncanny: A collection of Interdisciplinary Studies. London: Routledge.

- Jones, A.J.H. (2016). On South Bank: The production of public space. London: Routledge.

- Jones, C. (2017).This Is Our Voice: Coventry Independent Broadcast Co-Operative. (Unpublished Master’s report). Sheffield University: Sheffield School of Architecture.

- Jones, P. (2009). Putting architecture in its social place: A cultural political economy of architecture. Urban Studies, 46(12), 2519-2536.

- Jones, P. & Card, K. (2011). Constructing “social architecture”: The politics of representing practice. Architectural Theory Review, 16(3), 228-244.

- Koeck, R. (2013). Cine-scapes: Cinematic spaces in architecture and cities. London: Routledge.

- Kutbi, A. (2017). The Sponge Theatre: Theatre Re-Imagined as Public Realm Infrastructure.(Unpublished Master’s report). Sheffield University: Sheffield School of Architecture.

- Lashua, B. D. (2015) Zombie Places? Pop-Up Leisure and Re-Animated Urban Landscapes. In S. Gammon & S. Elkington (Eds.),Landscapes of Leisure: Space, Place and Identities.(pp. 55-70). Aldershot: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lashua, B.D. (2013). Pop-up cinema and place-shaping at Marshall’s Mill: Urban cultural heritage and community.Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 5(2), 123-138.

- Lashua, B. D. & Baker, S. (2014). Cinema beneath the stars, heritage from below. In J. Schofield (Ed.)Who needs experts? Counter-mapping cultural heritage.(pp. 133-145). Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

- Lefebvre, H. (1991[1974]).The production of space(D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans.).Oxford: Blackwell.

- Lefebvre, H. (1995[1962]).Introduction to Modernity: Twelve preludes, September 1959—May 1961. London: Verso.

- López-Sintas, J., García-Álvarez, M. E., & Hernández-López, A. G. (2017). In and out of everyday life through film experiences: An analysis of two social spaces as leisure frames. Leisure Studies, 36(4), 565-578.

- Maak, N. (2015).Living Complex: From Zombie City to the New Communal. Munich: Hirmer Press.

- Mould, O. (2017).Urban Subversion and the Creative City. London: Routledge.

- Mumford, L. (1938).The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt Brace.

- Pallagst, K. (2013). Shrinking cities: International perspectives and policy implications. London: Routledge.

- Peters, K. (2010). Being together in urban parks: Connecting public space, leisure, and diversity. Leisure Sciences, 32(5), 418-433.

- Romero, G.A. (Director) (1978).Dawn of the Dead(Motion picture). Los Angeles: United Film Distribution Company.

- Shepard, B. & Smithsimon, G. (2011). The beach beneath the streets: Contesting New York City’s Public Spaces. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Shirtcliff, B. (2015). Sk8ting the Sinking City. Interdisciplinary Environmental Review, 16, 97-122.

- Taylor, E. (2017).A Political Platform. (Unpublished Master’s report). Sheffield University: Sheffield School of Architecture.

- United Nations (2014). World Urbanization Prospects. Retrieved fromhttps://esa.un.org/unpd/wup/publications/files/wup2014-highlights.pdf

- Walters, T. (2017). Facilitating well-being at the second home: The role of architectural design. Leisure Studies, 36(4), 493-504.

- Wark, M.K. (2011).The beach beneath the street: The everyday life and glorious times of the Situationist International.London: Verso.

- Wong, W. (2017).Urban Beach Corridor. (Unpublished Master’s report). Sheffield University: Sheffield School of Architecture.